Inspiration; noun; Latin root: spirare; “to breath”

Definition(s):

- a divine influence directly and immediately exerted upon the mind or soul.

- the drawing of air into the lungs; inhalation

Each and every time you take a breath you are reestablishing a contract with the universe. Failure to constantly renew this contract will result in the annulment of life altogether, a thin line we all must carefully dance in order to maintain our existence. Despite its prevalence and importance, the breath has taken a backseat in the minds of many individuals today. Occupied by a torrent of stimuli, the mind of a 21st century human has had its priorities shifted on its head. The epidemic of stresses and anxieties that afflict the current generation is but a result of this priority flip. Regaining your breath means taking back your life.

Respiration is the means by which our physical bodies recruit atmospheric oxygen for energy, more specifically the electrons it provides. Death will occur mere minutes after oxygen supply has been cut off; as the ability for cells to exchange energy exchange halts and they begin to die, while not being replaced.

No matter the circumstances in life, your ability to respire will be the foundation for every activity you participate in.

If you can imagine life, and its necessities, as a pyramid, breathing would make the base of said structure. As you go up the structure the requirements for life would become more complex, but ever reliant on what supports them from below. If you wish to build a grand pyramid that is your life, you must begin by building a large, sound base. Further expansion of the pyramid upwards, without an adequate foundation, would lead to an eventual collapse. The same idea applies to your own life. You could be an immensely successful individual yet if your breath is compromised, you are living on borrowed time.

The reality is that our breathing not only provides us with the currency for life (electrons), but also aids in the motion of bodily fluids (blood/lymph/ventricular), as well as being critical for postural stabilization. Combined, these functions reassert that the breath is indeed the base of life and needs your utmost attention.

Your Breath and Your Posture

Few people recognize the influence of breathing on his or her upright posture. In the fitness community the ambiguous use of the words “core” and “abs” tend to dominate the topic. From the rectus abdominis, to the obliques, and then the transversus abdominis, disagreement exists regarding the true leader of torso stabilization.

This is where the problem lies, in the act of reduction. Attempting to break down the issue into its smallest possible component is neither sustainable nor effective. The truth of the matter is that the neuromuscular system rarely, if ever, works through isolation. Instead, there exists a coordination of different muscles that aim to complete a certain job. In the case of posture this job is the stabilization of the entire spine, from the hips to the head. It makes sense to think that the action of breathing is at the top of the list of priorities for the body. This means the breath is the most basic, and most required, muscular movement for life. As more complex actions are performed, the body simply adds to the chain of command, as any movement implies breathing. Rather ingeniously, the mechanism by which we breath also stabilizes our spine, shoulders, and hips.

Intrinsic Stabilization

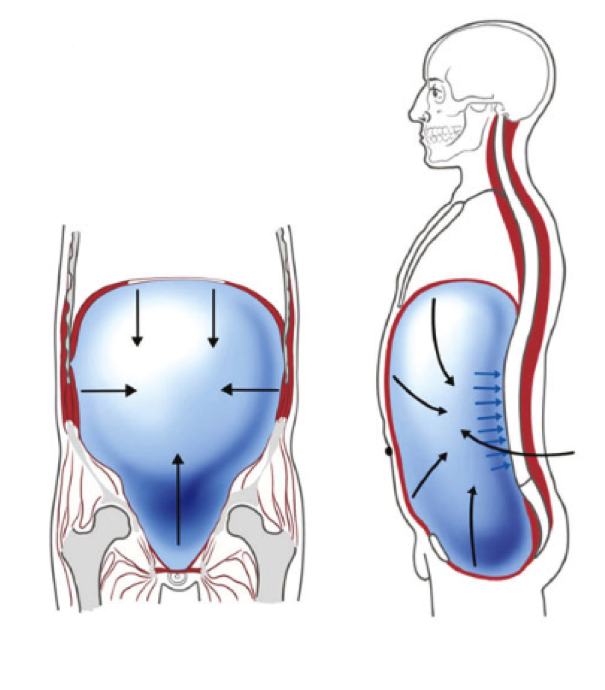

The act of breathing is dictated by a group of muscles known as the Intrinsic Stabilization Subsystem (ISS), one of a handful of muscle groups responsible for movement and bodily function (1). The ISS is comprised of the diaphragm, transversus abdominis, multifidus, and pelvic floor muscles.

These work in unison to create pressure within the abdominal cavity. The diaphragm is responsible for exerting pressure downward, as well as expanding the volume of the pleural cavity so that air fills the lungs during inspiration. Functioning similar to a piston, the contracting diaphragm pushes the viscera down so the the pelvic floor stretches slightly. Upon exhale, the pelvic floor contracts, diaphragm relaxes, and air is forced out of the lungs. Additionally, the transverse abdominal assists the pelvic floor in creating intra-abdominal pressure during an exhale. Meanwhile the multifidus helps to keep the spine in a slightly extended position, ensuring proper function.

The abdomen is situated in a strategic position between the two primary movers of the body: the shoulders and hips. It is for this reason stabilization of the torso is so important; if the shoulders and hips have a firm base to exert energy upon, greater muscular force can be applied. If the body lacks such a base of support then stabilization and/or movement must come from somewhere else in our anatomy. For short term scenarios this is not an issue, it is when practices like this become commonplace that problems arise. Breathing pattern disorders are linked to back pain and other physical pathologies for this very reason (2).

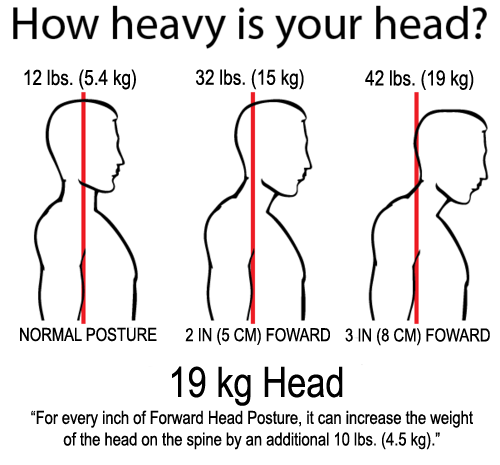

Although the abdomen is often the highlight of breathing, the upper chest and neck also contribute to inspiration. The most predominant muscles responsible for this action are the scalenes, sternocleidomastoid, and upper fibers of the trapezius. By elevating the rib cage, clavicle and scapula, the pleural cavity expands upward, decreasing pressure and inducing the inflow of air. Simultaneously these muscles help to stabilize the skull and the cervical spine. Given the weight/importance of the skull and brain, balancing the head is critical to total body posture.

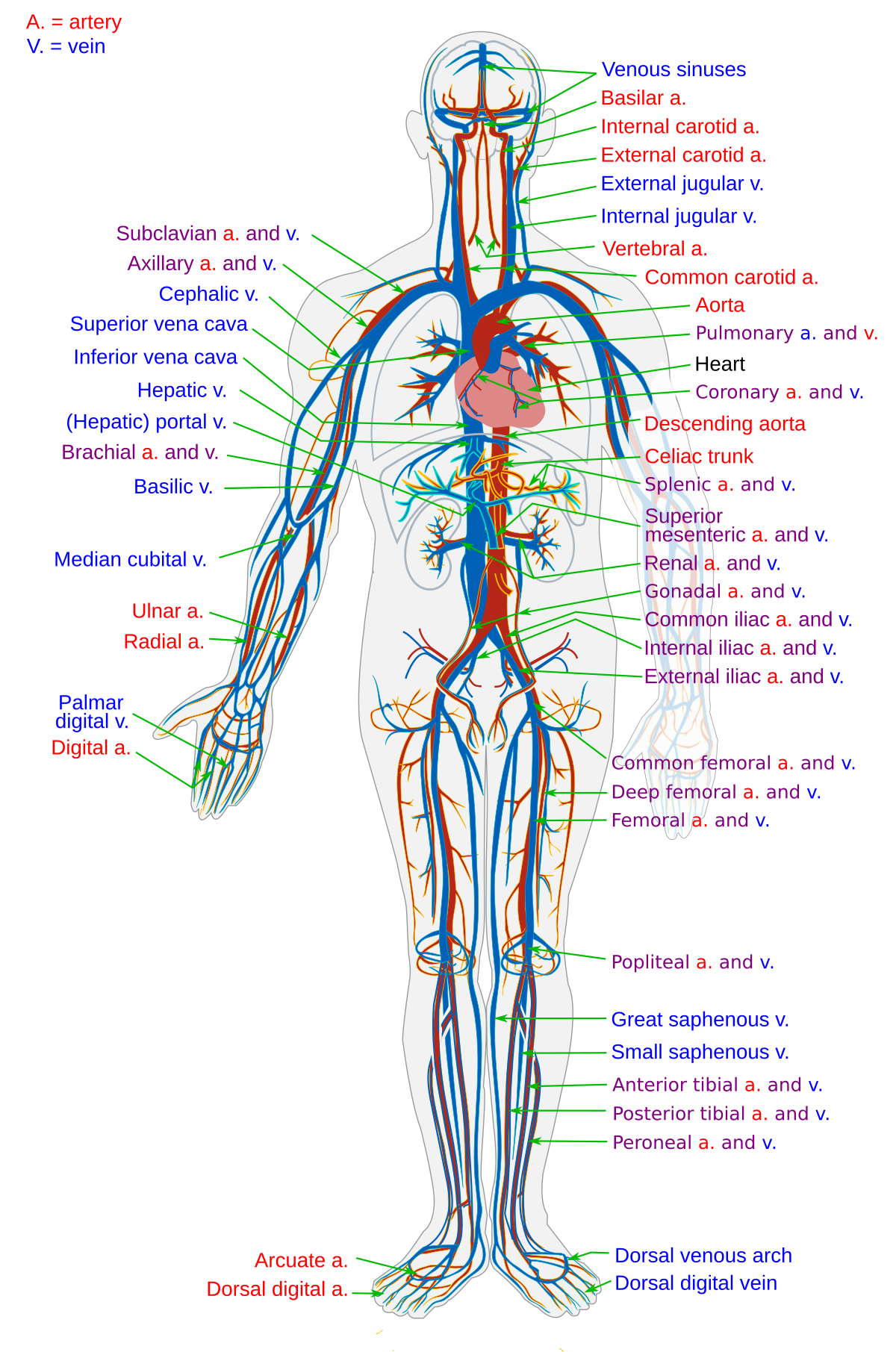

A Second Heart

Your physical body is composed of approximately sixty percent water. That water is not only found within cells but comprises a large portion of ones blood and lymph fluid. These two bodily systems aid in the flow of nutrients and the removal of waste to parts of the body. Though blood is primarily pumped by the heart, muscular contractions aid in the process of moving both blood and lymph. Known as the skeletal muscle pump, the simultaneous contraction and relaxation of muscles force blood out of and into various part of our body. The vacuum nature of the two systems allows for this to happen with relative ease.

In regards to breathing, the same muscles that allow us to inhale and exhale provide us with help in the regulation of systemic blood pressure. The central location of the breathing musculature –around the descending aorta and the inferior vena cava — ensures that this balance of fluids is maintained between the legs, torso, arms, and head, across a variety of movements and positions. It is by these means that we can go from a seated position, to standing, and not pass out from the blood rushing to our legs. Each inhale and exhale is itself a pump, just like that of the heart (3).

Taking this idea, fighter pilots are outfitted with specialized suits to deal with the rigors of flight. These suits are comprised of air chambers that increase in pressure. Similar to skeletal muscles, the suit helps to maintain even blood distribution amidst intense changes in gravitational forces.

Though blood is one of the more well known bodily fluids it is not alone. Lymph, serves the immune system, acts as a means to transport fats, and removes cellular waste. Unlike blood, the lymphatic system does not have a designated pump such as the heart. Instead, the ducts must rely on the physical contraction of muscles to mobilize the fluid (4).

Because both blood and lymph rely on diffusion to transport nutrients/waste it is critical that movement of these liquids is steady and constant. This means that when one is stationary, the breathing musculature must pick up the slack to mobilize bodily fluids. Failure to do so may result in the body operating well below peak efficiency, and susceptible to disease.

The evidence for this statement lies in the rates of chronic disease among those who are inactive. Not moving is one of the most detrimental behaviors one can have in life, more deadly than smoking, and actually having a chronic disease. If movement implies (elevated) breathing then we know that the breath must have a hand in all of this. Just how much is not known.

Perhaps the least well known liquid in your body is the Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This fluid encases the brain and spinal chord acting as a means of nutrient exchange and physical protection for such precious parts of our body (5). Although not directly impacted by the respiratory muscle pump, the position of the spine and head determine the rate of flow, and therefore how well nurtured our brain and spinal chord are. Knowing that the breath has a hand in the stabilization of the spine, it then follows that it influences the flow of CSF.

So, the integrity of our nervous system, along with all other tissues in our body are dependent on breathing. Though a simple action, the breath has a far reaching influence on our well being.

Energy Supply

Last but certainly not least, the most important task of the respiratory system is to provide our body with the electrons necessary for life to occur. These electrons come in the from oxygen in the air and act as the currency for cellular energy exchange. Each cell in your body is an engine that runs on the energy provided by oxygen. This oxygen is taken from the air via diffusion into the blood vessels, while carbon dioxide –a product of cellular respiration– is simultaneously released back into the atmosphere.

This simple exchange allows is what allows us to continue maintaining homeostasis and thereby life. If you were unable to breath for longer than 5 minutes, the energy supply to your body/brain would be choked off and death would occur. Anyone can realize the importance of such an issue by holding his or her breath for longer than a minute. Without training, the mind enters a state of utter panic and fear, prompting you to take a breath. This feeling would not exist if not for the dire situation one faces when deprived of oxygen.

More oxygen is not necessarily an indicator of better or more health as a too much oxygen can be just as harmful. There exists a balance, a state of equilibrium, that must occur for health to be optimized. In this state, energy exchange is happening at rates that induce proper amounts of cell division and cell death. This means that there must be a balanced ratio of inhalation and exhalation, as too much of one would actually be harmful to us.

Breathing and Stress

Breathing, and the perception of stress share an intimate relationship. Upon a stressful stimuli, one will often raise their rate of respiration, thereby increasing the rate of energy uptake. In theory, this provides more oxygen for cells to utilize during times of great need, say a conflict with a predator or competitor. When this stress disappears, breathing returns to a slower rate, as less oxygen is necessary.

Though regulated through the Autonomic Nervous System, which is thought to not be under our conscious control, the physical act of breathing is entirely controllable. Breathing in a slow, relaxed manner will induce parasympathetic (rest/digest/reproduce) nervous pathways. Conversely, hyperventilating leads to stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system (6). One must imagine breathing as the lead horse in a team, where it goes the others will follow. Those other horses being the rest and digest functions of the parasympathetic nervous system or the fight or flight sympathetic pathways.

If an individual has little control over his or her breathing, he or she has little control over how they respond to stress. A lack of breathing discipline can then induce chronic states of fear and anxiety. Worse, this emotional fear is transmuted into physical pathologies as a stressed state forgoes long term processes such as digestion and tissue repair for energy production and tissue breakdown. Evidence shows that dysfunctions in the Autonomic Nervous System –such as sympathetic dominant states (stress)– can lead to a range conditions, from kidney failure, chronic pain, hormone dysfunction, and digestive issues (7).

Impairments to the Breath

Just how do these issues in the ANS come to be? There is no single definitive answer, but a spectrum of possibilities. Past and present emotional and physical trauma are the two main culprits in this situation. If a mentally scarring event has taken place, reinforcement of sympathetic pathways may result in a stressed state being the predominant mode of existence. Additionally, physical damage to the nerves that innervate parasympathetic functions, such as breathing, can force the body to communicate via the sympathetic highways.

The most widespread example of this physical issue is the impingement of nerves in the cervical spine. Serving the actions of breathing, along with swallowing, and talking, these nerves are subject to both atrophy and impairment (8). One’s head position can place undue physical stress upon these nerves causing dysfunction. Living in this condition will result in improper breathing among other serious health implications.

The Iceman

Wim Hof, a Dutchman that holds multiple world records in the realm of cold tolerance, attributes his accomplishments to the conscious control of his breathing patterns. His ability to spend extraordinary amounts of time in the cold was so phenomenal it prompted interest from the scientific community. It was under scrutinized documentation that it was found that Wim Hof, the Iceman, was actually able to not only increase his body temperature amidst freezing temperature, but suppress his body’s natural immune response to an endotoxin. While more research has yet to be done, Hoff claims that his practice can fight cancer, among other chronic diseases (9). Though that might sound far fetched, the logic and possibly soon, the evidence, is on his side. He is living truth of the power of one’s breathing.

Breathing is Medicine

Your own body is the most adept healing machine known to mankind. No drug, surgeon, or therapy, can even come close to competing with the healing powers of our intrinsic repair system. Each and every day your body destroys thousands of cancer cells, wards off billions of pathogens, and all the while replacing innumerable cells that have died along the way. It is when the physical power supply to this system, along with its means of delivery, is choked off that problems arise. In short, when you are breathing is compromised, so is you entire body.

The simplest and most powerful action you can perform at any given moment is a deep, steady breath. As your lungs fill with air, energy is taken in and waste returned to the atmosphere; your spine is aligned and stabilized; finally, blood and lymph are moved throughout the body. The combination of such an action ensures a physical being with the ability to maintain homeostasis and thereby continue life.

If you are performing this function at a reduced efficiency, you are essentially living a reduced form of life. It is time to take back what you have been leaving on the table and breathe. Life is crazy, but breathing isn’t; control what you can control.

Citations

- Intrinsic Stabilization Subsystem (ISS). (2019, March 23). Retrieved from https://brentbrookbush.com/articles/corrective-exercise-articles/core-subsystems/intrinsic-stabilization-subsystem/

- Low Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain_and_Breathing_Pattern_Disorders

- Miller, J. D., Pegelow, D. F., Jacques, A. J., & Dempsey, J. A. Skeletal muscle pump versus respiratory muscle pump: modulation of venous return from the locomotor limb in humans. (2005). The Journal of physiology, 563(Pt 3), 925–943. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076422

- Zawieja D. C. (2009). Contractile physiology of lymphatics. Lymphatic research and biology, 7(2), 87–96. doi:10.1089/lrb.2009.0007

- National Institutes of Health (December 13, 2011). “Ventricles of the brain”. Nih.gov.

- Jerath, R., Edry J.W, Barnes, V.A., and Jerath, V. Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: Neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. (2006). Medical Hypothesis, 67, 566-571.

- Fogoros, R. N. (2019, March 27). Dysautonomia Is a Family of Misunderstood Disorders. Retrieved from https://www.verywellhealth.com/dysautonomia-1745423

- C, F., Df, L., M, M., & De, H. (2017). Increased Telomere Length and Improvements in Dysautonomia, Quality of Life, and Neck and Back Pain Following Correction of Sagittal Cervical Alignment Using Chiropractic BioPhysics® Technique: A Case Study. Journal of Molecular and Genetic Medicine,11(2). doi:10.4172/1747-0862.1000269

- Kox, M., van Eijk, L. T., Zwaag, J., van den Wildenberg, J., Sweep, F. C., van der Hoeven, J. G., & Pickkers, P. (2014). Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(20), 7379–7384. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322174111