Sight, smell, sound, touch and taste. For some time it was thought that our sensory perception of the environment was limited to these select few senses. Although accepted by many, that belief is currently being threatened by new research. This research tells us that the gastrointestinal tract is composed of a diverse and thriving ecosystem, has the ability to function separate from the brain, but lastly, contains an unusual concentration of sensory neurons.

Yes, the majority of neurons that lie within what is known as the enteric nervous system are afferent in nature (1). Afferent nerves take information from the environment and send them to the CNS; efferent nerves send information from the CNS to peripheral nerve tissue. This means that the gut relays information from the environment to both itself and the rest of the central nervous system, primarily the brain.

Perhaps the age old adage of “going with your gut” is actually a truthful statement. We all can relate to this saying as we have experienced this phenomenon more than once in our lives. It goes to show that we may have more unknown influences operating beneath our conscious being.

Why?

It can be strange to think that the gut, a group of organs responsible for digesting food, also plays a role in how, and what, you think. But that is exactly the reason for this seemingly anomalous feature. Food, — along with air, and water — is our literal lifeline. Without food or water for more than a few days and we will suffer the fate of death. Although the digestive system does indeed break down food into usable nutrients, it cannot acquire food without help from other parts of the body.

As humans we must go out in search of food, and we use our nervous system to do so. The motivation, coordination, and execution behind such actions are regulated by one’s brain, spinal chord, and peripheral nerves. To pinpoint the exact physical and chemical needs of the body, the nervous system must be in communication with the digestive tract at nearly all times. After all, neither would exist without the help of the other, true interdependence.

To better imagine the gut’s influence on the nervous system think back to the last time you did not eat for a prolonged period of time. What happened to your stream of thoughts when hunger was presented to your body? Did you have the presence of mind to acknowledge the thoughts and move on? Or does the feeling of hunger get the best of you, thereby influencing your actions and emotions?

Better yet, have you ever been struck with cravings for a certain food and/or nutrient? Salty? Savory? Sweet? Chances are, you have experienced this occurrence more than one time in your life, and perhaps even every day for that matter. This occurrence is an example of the direct communication between your brain and your other brain. Your cravings are but the manifestation of a nutritional need within your conscious mind by your gut.

If we did not have this ability, we would most likely die. Without any desire, or knowledge of what we need to eat, nutritional deficiencies would arise. Over time a limited supply of nutrients would manifest themselves as various diseases, and eventually death. For this very reason, your gut must be able to direct the brain to obtain such life sustaining compounds.

How?

Known as the Gut-Brain Axis, a rather large bundle of nerve fibers connect the gastrointestinal system with the central nervous system giving birth to what is also called the enteric nervous system. This system, though technically a division of the so called autonomic nervous system, is capable of independent function — lending to the name “second brain”(2).

The number of neurons found within the gut also lends to the importance of gastric motility. How well the former food travels through the gut and absorbs into the body comes down to the contraction of smooth muscle along the intestinal tract. This process is almost entirely subconscious as well, meaning we do not have to think about digestion.

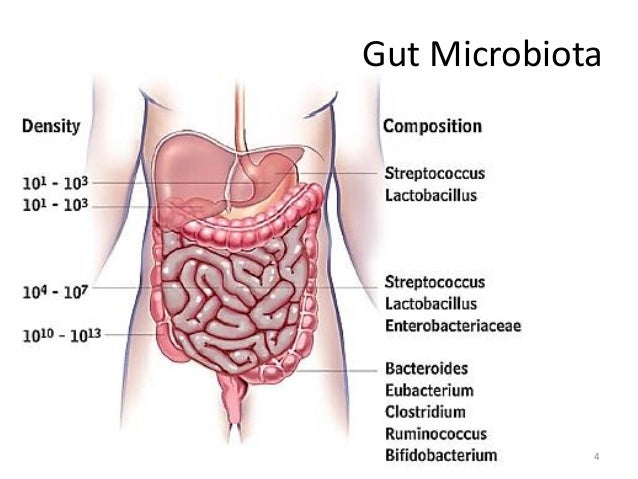

Intertwined between both the brain and the second brain (the gut) lie a substantial amount of microscopic organisms. These bacteria live symbiotically within each and every one of us, and perform tasks otherwise impossible for our physiology. These tasks include the synthesis of essential compounds from the food we eat (3). From these vitamins we are able to maintain various bodily processes, and thereby homeostasis with greater ease. It follows then that without a healthy ecosystem, our body cannot be effectively provided with certain important nutrients, and will therefore suffer the consequences. These consequences can be life threatening, though rarely in the short term.

There exist upwards of 2,000 separate species of various microorganisms that reside within us at any given point in time (4). This translates to some trillions of individual organisms all in the gut alone. Primarily within the Colon (large intestine) these forms of life produce nearly 90 percent of serotonin found within the body (5). Serotonin being an important neurotransmitter and hormone in regards to mood, motivation, and well-being. It follows then that a poor diet, and a reduced microbiome, are risk factors in a number of psychological pathologies including depression, anxiety, autism, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s (6,7). Not confined to the psyche, the consequences of a sick microbiome can indeed result in metabolic conditions, cancer, and heart disease as well. (8)

Implications

It is clear that the health and integrity of your digestive tract, and the organisms who call it home, is a significant pillar in the temple of health. With disturbances to either, an individual can expect a range of mental and physical ailments to follow. Because of the spectrum of possible symptoms, the condition can be hard to diagnose from a traditional medical mindset. It is for this reason that even an industrialized country such as the United States can suffer from such an epidemic of chronic disease.

The combination of a compromised diet, and a reductionist approach to health is to blame for such an issue. Foods that have been hyper-processed, as a means to further profit margins, are one of the culprits in regards to diet. Made to be sold, and not necessarily eaten, these processed foods fill eating establishments — and line the shelves of grocery stores — as an enticing trap for a hungry customer. Often devoid of fiber (the primary nutrient for gut organisms) these processed foods are but calories and calories alone. The prospect of easy energy is one the brain (and gut), developed over eons of food uncertainty, have a hard time ignoring. So great is this influence that one can be coaxed into eating something that is poisonous, yet fulfills a seemingly important goal.

A lifetime spent eating these “foods” take a toll on our physiology. Without vitamins and enzymes crucial chemical reactions cannot occur within us. The excess calories, that cannot be used for said processes end up being stored as fat. Worse yet, the lack of fiber starves the ecosystem inside of our intestines, leaving us without vital neurotransmitters among other vitamins and compounds.

It is in this weakened state that we are vulnerable to the likes of chronic disease. As other environmental stressors, piled on top of an insufficient diet, test the healing capacity of our bodies. If we are not ready to meet this challenge it could get the best of us, with possibly fatal consequences.

For these reasons all speak on the importance of our digestive tract, and its role as a sensory organ. If it could not sense dietary needs, we could not

Caring for the Gut

Taking care of one’s gastrointestinal tract is a full time job. However, this job pays with the priceless benefits of health, happiness, and security. The simple tandem of a proper diet and reduced stress will allow ones gut to flourish.

What is a proper diet?

A diet that supports the gut is one that is rich in fiber, balanced macronutrients, and fermented foods. Combined these ingredients support a rich habitat where helpful organisms do the dirty work for us. With their help we are able to absorb nutrients and vitamins to keep life going.

Why Stress?

Reducing stress is essential because of the body’s reaction to a perceived stressful event. During a fight or flight (sympathetic) response, blood flow to the gut is constricted thus slowing digestion (). In certain circumstances this is absolutely necessary, yet living like this for too long can inhibit adequate digestion. A feedback loop ensues when the gut’s inhabitants starve from lack of nutrients, thus prolonging stressful states.

Reducing stress means stimulating the parasympathetic (rest and digest) nervous system, allowing for improved nutrient uptake. In time, this state will help cultivate a well running digestive tract, along with a healthy ecosystem inside of it. The result being a healthier you.

Get In Touch With Your Sixth Sense

If you take time to appreciate and care for the wonder that is your physical body, you will be rewarded with the gift of health. Just as you look after your eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and skin, look after your gut. A life devoid of a healthy gut is one at the mercy of disease, don’t let that be you.

References

- Costa M, Brookes SJH, Hennig GWAnatomy and physiology of the enteric nervous systemGut 2000;47:iv15-iv19.

- Gershon, M. D. (1999). The Enteric Nervous System: A Second Brain. Hospital Practice,34(7), 31-52. doi:10.3810/hp.1999.07.153

- Rowland, I., Gibson, G., Heinken, A., Scott, K., Swann, J., Thiele, I., & Tuohy, K. (2018). Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. European journal of nutrition, 57(1), 1–24. doi:10.1007/s00394-017-1445-8

- Thursby, E., & Juge, N. (2017). Introduction to the human gut microbiota. The Biochemical journal, 474(11), 1823–1836. doi:10.1042/BCJ20160510

- Martin, C. R., Osadchiy, V., Kalani, A., & Mayer, E. A. (2018). The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cellular and molecular gastroenterology and hepatology, 6(2), 133–148. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.04.003

- Kowalski K, , Mulak A. Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019;25:48-60. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm18087

- Bruce-Keller, A. J., Salbaum, J. M., & Berthoud, H. R. (2018). Harnessing Gut Microbes for Mental Health: Getting From Here to There. Biological psychiatry, 83(3), 214–223. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.014

- Zhang, Y. J., Li, S., Gan, R. Y., Zhou, T., Xu, D. P., & Li, H. B. (2015). Impacts of gut bacteria on human health and diseases. International journal of molecular sciences, 16(4), 7493–7519. doi:10.3390/ijms16047493