:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/library/7635/qR2r7brI9NTRXQjnSWmP1Q_Os_sphenoidale_01.png)

There exists a single small bone in your skull that has the ability to change the way you experience life. The sphenoid bone is a vital piece of our anatomy that lies at the junction of the face, skull, and spine. With a hand in posture, stress, sleep, breathing, chewing, and swallowing, the sphenoid’s influence spans across our entire existence. Improper function of the sphenoid can result in a number of conditions ranging from a nuisance to completely debilitating. Bringing awareness to the sphenoid and its many functions can help unlock aspects of your life that you may have not even thought possible. Tapping into your full potential physically, mentally, and spiritually is dependent on the health of your sphenoid bone.

What is it?

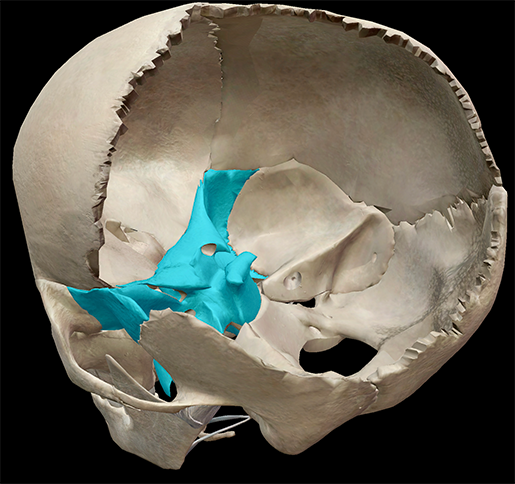

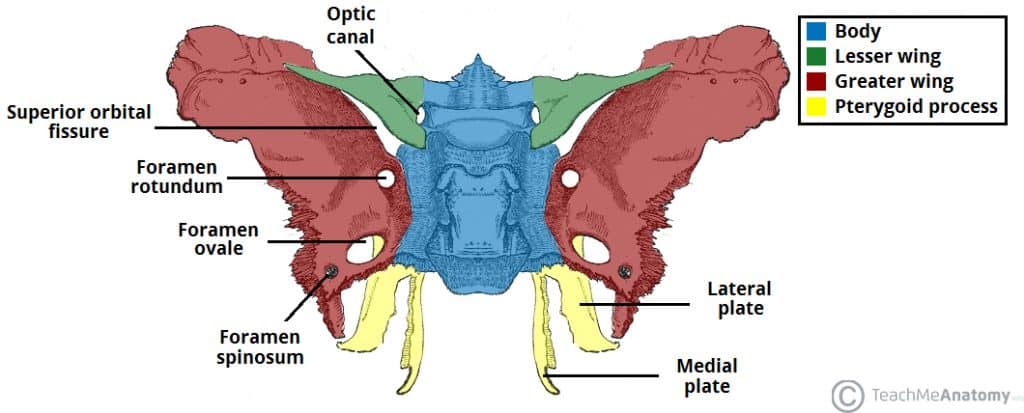

The sphenoid bone is a butterfly shaped bone that resides at the junction of the face and the rest of the cranium. Acting as a keystone, (“sphe-” translates to “wedge” in Latin) the sphenoid bears the weight of other facial bones and holds them in proper position against the force of gravity. Its position allows it to ever so slightly articulate with the twelve bones that make up the mouth, nose, eyes, ears, jaw, as well as base of the skull. With so many points of contact, dysfunction at the sphenoid bone can result in issues of each of the corresponding parts of the body. This means your vision, sense of taste, ability to breathe, and balance/posture are all influenced by the sphenoid and its position in space.

How?

What is the logic behind the sphenoid bone’s influence on one’s upright posture? How does a bone in the face affect the position of your spine. The answer lies in the proximity of the bone to the temporomandibular joint –where the jaw meets the skull– and the atlanto-occipital joint –where the skull meets the spine. It is at these junctions that a massive portion of our upright posture literally hinges.

Atlanto-Occiptal Joint (AOJ)

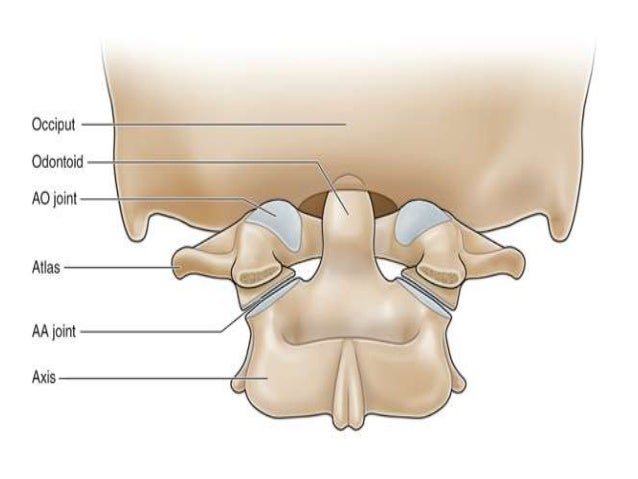

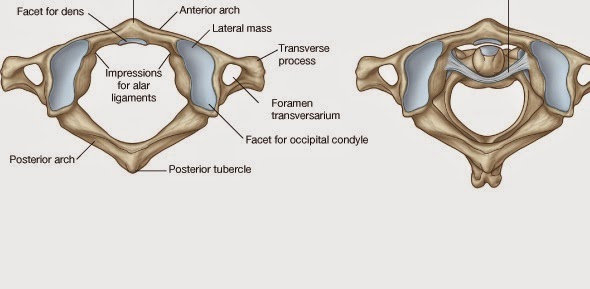

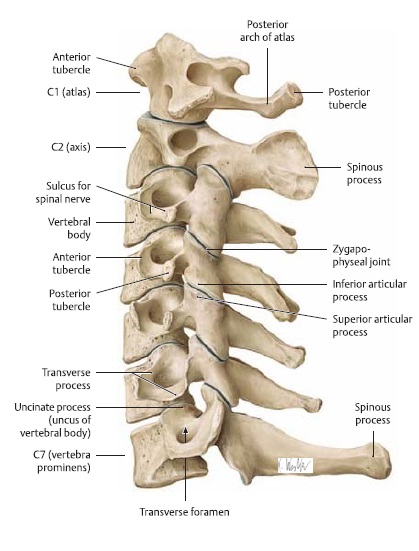

The conjunction of the skull and spine occurs where the occipital bone meets the first cervical vertebra, known as the atlas. The occipital bone is able to pivot on the atlas, mainly through flexion/extension and lateral deviation (forward/backward; tilting to the side). The shape of the atlas allows for significant freedom of movement as occipital bone slides atop the smooth condyles of the first cervical vertebra.

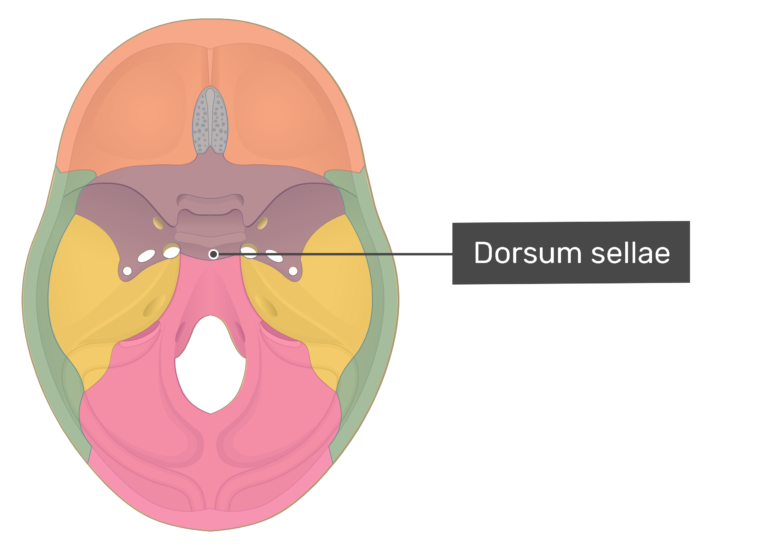

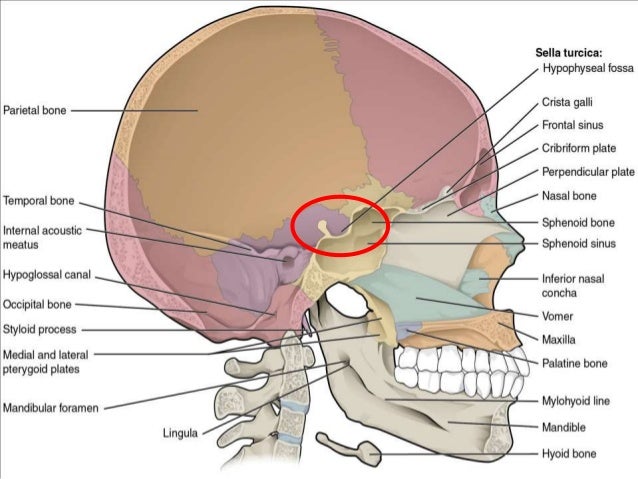

Dorsum Sellae

Adjacent to the atlanto-occiptial joint is the posterior surface of the sphenoid bone, the dorsum sellae (Latin for “rear seat”). The name is a direct description of the surface where it meets the occipital bone. As it implies, the sphenoid bone and occipital bone are able to pivot very slightly against each other. This means that these two areas of our physiology can and do influence each other physically. What happens at the first cervical vertebra will in fact alter the position of the sphenoid bone, and thus the face.

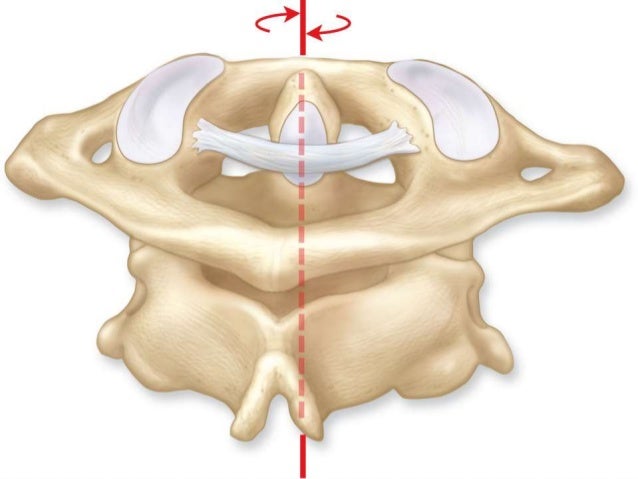

Atlanto-Axial Joint (AAJ)

Below the atlas lies the axis, the two creating what is known as the atlanto-axial joint. The atlas (C1) and axis (C2) are the first and most mobile vertebrae of the cervical spine. The atlas permits flexion and extension from the cranium, while rotating atop of the axis. Due to the mechanics of these two vertebrae in relation to that of the other bones in the neck (C3-C7) the majority of movement of the cervical spine must come from the AO and AA joints. If the sphenoid is out of position, the next links in the chain– the AA and AO joints– will be forced to compensate, cascading into a reaction that could span the length of the cervical spine. Worse yet, this compensation could manifest elsewhere along the entire spine.

Temporomandibular Joint

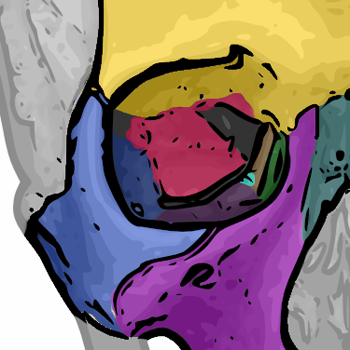

The jaw (mandible) meets the skull (temporal bone) at the so called temporomandibular junction (TMJ). Although the sphenoid bone does not directly touch the mandible it does border the temporal bone, and serves as an attachment point for muscles that insert onto the mandible. These muscles include the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles (Classical Greek for “wing”) as well as the temporalis mucle.

The pterygoids assist in both the elevation and depression of the jaw as well as the lateral deviation (side to side motion) that occurs when chewing. Most of all these two sets of muscles (pterygoids) induce protraction of the mandible, a necessary function that grants the intricate structures located proximally to the joint — the ear, along with a number of nerves and blood vessels — the freedom to operate.

Although somewhat esoteric, the sphenoid’s relationship with the mandible also plays a role in keeping us upright and stable. In fact, both the tongue and jaw have been shown to directly influence one’s ability to generate power in a series of weightlifting exercises (1). It is estimated that 30-40% of our ability to generate power hinges at this point in our physiology. This makes sense as both the jaw and tongue are manipulators of the position of the skull atop the spine. The skull, essentially being a bowling ball atop a flexible rod, determines where the rest of the spine will articulate– where the skull goes the spine will follow. If the skull is out of position, the rest of the spine must compensate in order to maintain upright posture against gravity, thus greatly reducing mechanical efficiency.

The proximity of the sphenoid bone to so many critical junctions in our anatomy lends to it being a powerful manipulator of how we are able to carry ourselves. Physically, the sphenoid plays a significant role articulating with the occiput, supporting movement of the mandible, and influencing the function of both the eyes and ears.

Soft Tissues

Although physical integrity is crucial to maintaining upright posture, there exist other soft tissues adjacent to the sphenoid and temporomandibular joint. Included in this bunch is the trigeminal nerve, the facial nerve, and the internal carotid artery. When the mandible exists in excessive retraction the bone can impinge the neurvovascular bundles. With restricted nerve and blood flow these vital structures can slowly begin to atrophy. In time this leads to a positive feedback loop where the degeneration of muscles leads to further impingement of the neurovascular bundle. If these vital parts of our anatomy are disrupted a great number of negative changes can occur. Dystonia, Tourettes, vertigo, tinnitus, along with excruciating pain are but just a few symptoms of temporomandibular dysfunction (2). Other issues can manifest as postural abnormalities, difficulty eating/swallowing/breathing/speaking, excessive teeth grinding, and sleep apnea. It is thought that close to one in every three– although likely much higher –people experience this phenomenon at least once in their life. If left unchecked, the condition can spiral into further degradation of the joint, along with the surrounding tissues.

Included in the impingement is the auriculotemporal nerve (a branch of the trigeminal) (2). The AT nerve directly innervates the vestibule and the cochlea, the balancing mechanisms of the inner ear. Part of the vestibular system, this part of the body is responsible for helping us maintain balance, in conjunction with vision. These fluid filled chambers of the inner ear detect the change in the level of the liquid, and relay said information to the brain. If the AT nerve is impinged, so is our ability to balance ourselves effectively.

Foramena

Besides acting as both physical and muscular supports the sphenoid bone contains tunnels through which numerous nerves and blood vessels of the face, mouth, and tongue pass through. These features are known as foramena (Latin for “holes”). The foramen of the sphenoid include:

The trigmeninal, optic, and glossopharyngeal nerves all have branches that pass through the sphenoid bones by way of their respective foramena. These nerves and blood vessels supply the eyes, nose, mouth, tongue, face, facial muscles, and masticatory muscles. When the sphenoid bone is moved out of position it can place physical strain on these tissues, potentially leading to a number of physical, and possibly even psychological issues down the line. Pain, or impairment of the affected senses/muscles could be a symptom of a sphenoid being out of position.

Homonculus

Another implication of the sphenoid bone is its influence on proprioception. Proprioception is our conscious ability to detect our body in space and is related to the relative concentration of nerves (and dedicated brain space) throughout our physiology. To understand the impact the sphenoid bone has upon our perception of life one should be aware of what as known as the “sensory homonculus”, a caricature that depicts the human form in relation to the amount of nerves and dedicated space in the brain. This is how we perceive the world to be, with our eyes, nose, hands, tongue and mouth occupying a substantial portion of we know as reality. The sphenoid, being a gateway for the nerves to the eyes, nose, mouth and lips has its fingerprints over a large portion of our conscious perspective.

While many people are under the impression that our ability to maintain upright posture is solely dependent on the strength of muscles, the reality is more complicated than that. It is the subconscious processes that make us aware of our body’s position in space that have an underrated influence on posture. In translation, poor postural position should be corrected through the optimization of this perception of ourselves. Without doing so, attempts at strengthening various parts of the anatomy will be in vain.

Sphenoid-Pituitary Relationship

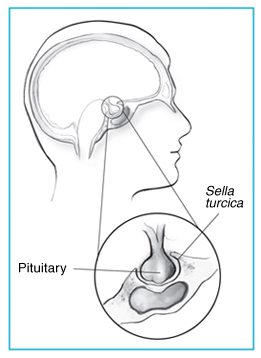

The pituitary gland, a small organ resembling a bean, in regards to both size and shape, is referred to as the master gland in the body. Tied closely to the hypothalamus, the pituitary is at the center of the neuro-endicrine axis, where the nervous system and the endrocrine system coordinate with one another. Such a juncture is absolutely vital for hormone secretion, the chemical backbone of our health and our ability to maintain homeostasis. The pituitary secretes the following hormones: growth hormone, prolactin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, adrenochorticotroic hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, antidiuretic hormone, oxytocin, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone. These hormones are the essential in dictating the body’s response to environmental stimuli. How you react to stress is greatly influenced by the pituitary gland and its .

What does this have to do with the sphenoid bone? The pituitary gland is actually almost entirely encased within the sphenoid bone. Known as the sella turcica (“Turkish seat” in Latin) this feature is quite peculiar, but far from an accident.

Stimulating the Pituitary Gland

Given the sphenoid bone’s relationship with the nose and the proximity of the pituitary to the sphenoid sinus it reasonable to assume these parts of our anatomy influence each other. How? Each and every time you breath you are gently vibrating your sinuses ever so gently. Such an action stimulates blood flow to the numerous capillaries in the region. Located next to the sphenoid sinus, the pituitary gland is undoubtedly a recipient of this improved circulation from the sinuses.

The act of humming, which involves the tongue shifting into its natural position against the maxilla (roof of the mouth), is one way to intensify these effects. Humming itself has been shown to improve symptoms of inflamed sinuses, likely due to the increase in blood circulation to the area (3). There currently exists little research on the matter, in part due to the lack of financial incentive on the topic. However, there is research that shows snoring during sleep does negatively influence the amount of growth hormone –a hormone secreted at the pituitary– present in an individual (4). Snoring is the process of improper jaw and throat position during rest. The jaw is often retracted and opened, causing the individual to breath using the mouth. Such an action closes the airways of the throat, inducing the reverberating snore we are all familiar with. Additionally, there are documented instances of sphenoid sinus inflammation inducing dysfunctional prolactin secretion, another hormone made in the pituitary.

By breathing in a manner that utilizes the entire sinus caverns, the pituitary gland can be stimulated. In turn your body’s attempt at homeostasis, and how you handle stress could very well improve.

Sphenoid-Pituitary-Pineal Relationship

Tied closely to the pituitary gland is the pineal gland. Regarded as the third eye, seat of consciousness, and interface with higher dimensions, the pineal gland is an essential organ in our body. Melatonin, the primary neurological antioxidant, is a hormone secreted by pineal gland that acts to repair nerve tissue that has been damaged by environmental stress. This is why sleep is so important for our ability to maintain homeostasis; in fact, a lack of sleep will kill you far before a lack of food does!

Although not much is known about the pituitary-pineal axis it is known to certainly influence one another (5). There is evidence to suggest that these two glands are intertwined with one another which makes sense as they both are involved with the synchronization of hormones and the nervous system.

Sphenoid Bone and Breathing

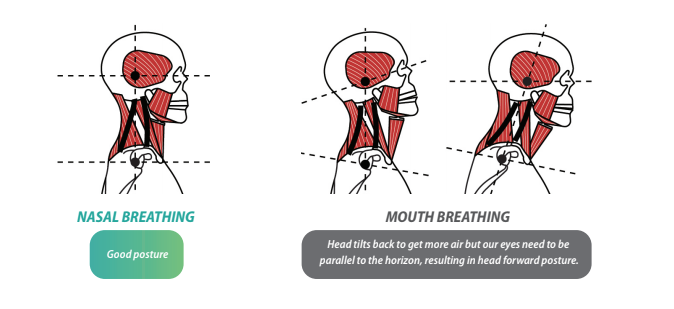

Breathing is yet another vital bodily function that the sphenoid has its metaphorical hand in. The reasoning behind this lies in the sphenoid’s relationship with the the jaw and the nose. In theory, noses are the primary breathing apparatus of humans. This becomes clear when one is able to appreciate the size of the sinus caverns located with the skull. Though this is ideal, the reality is that for a variety of reasons many people in today’s world have become mouth breathers. While there is no distinct cause– outside of postural dysfunction –mouth breathing can wreak havoc upon those who practice it constantly.

Such a term has been a derogatory term for ages, and for good reason. Breathing with the mouth cascades into a number of actions by the body: the mandible retracts, head and shoulders slump forward, and the face has the appearance of melting down towards the ground. What should be happening is an air tight seal at the mouth. Accomplished by the lips, tongue, and soft palate, a vacuum seal gives the nose the maximum amount of suction when inhaling. If this seal is broken then the nose must work harder for even less air, or the mouth must be opened to compensate. As alluded to earlier, breathing with the nose actually stimulates growth hormone secretion, and even nitric oxide production, two valuables molecules for human health and well-being.

The pterygoids shift the jaw forward, allowing the tongue to rest on the hard palate. In this position the lips are also able to lie in a relaxed position well in front of the incisors. Combined with the soft palate, which originates at the sphenoid these physical actions are what help to create a vacuum seal at the mouth for the nose and thereby maximize suction. Without this vital vacuum, the process of breathing is strained and can become compromised. Not only can this mean postural abnormalities, but given the breath’s influence upon all physiological and psychological processes can seriously impair quality of life.

Sphenoid Bone in Chewing and Eating

Chewing

The sphenoid bone serves an attachment point for the pterygoid muscles along with the temporalis muscle, the largest and most powerful muscle of mastication. In action, the pterygoids depress, elevate, protract and laterally deviate the mandible. Conversely, the temporalis retracts and elevates the mandible to crush, slice, and tear food. These muscles work dynamically, opposing and working with one another to help break down bits of food into smaller more readily digestible pieces. Additionally, because the sphenoid bone’s relationship with the trigeminal nerve, other muscles of mastication including the masseter (the strongest muscle in the body) can become inhibited as well. Over time, impaired chewing ability can lead to inhibited digestion, leaving precious nutrients on the table at all times.

Swallowing

Additionally, the sphenoid acts as the origin for the tensor veli palatini, a muscle responsible for tensing the soft palate. This action helps to prevent food from entering the nose, as well as helping to equalize pressure in the ears.

Lastly, the superior pharyngeal constrictor originates at the medial pterygoid plate of the sphenoid. This muscle is partially responsible for the act of swallowing as well. The vagus nerve— the primary nerve of parasympathetic (rest and digest) functions– innervates the superior pharyngeal constrictor. The vagus nerve is involved in the subconscious stress response as it supplies all organs from the neck down to the colon. If there is some form of physical dysfunction at the sphenoid it could mean a vagus nerve issue, or vice versa.

Potential Fixes/Treatments

There is no quick fix to a dysfunctional sphenoid bone, but long term practices that can help restore proper function. The utmost important of all of these is practicing good breathing posture– as good breathing position cannot be achieved without both mouth and body posture. At the same time how we chew and swallow our food does have a role in how

Breathing Posture

Breathing posture is the position that allows for the most efficient gas exchange during the acts of inspiration and expiration. This requires the simultaneous positioning of the mouth, jaw, head, neck, and torso in order to maximize potential air intake. In all this includes a shut mouth and a relaxed, supple spine. Known as a lotus position in yoga, this seated, cross legged posture is ideal posture for respiratory exchange and efficiency. Practicing this position for 10-20 minutes each day can do wonders for your natural breathing patterns.

Given that the breath is the most important and most frequent muscular movement, it forms the foundation for our neuro-muscular operating system as each and every other muscular movement implies inspiration and expiration. Breathing with an open mouth, and utilizing improper musculature will result in slight adaptations by the body. These adaptations can shift the position of the keystone that is the sphenoid, cascading into the number of the consequences described above. For many people, their bad posture is not caused by some form of muscular weakness but years of poor breathing habits ingrained with his or her nervous system.

Chewing Habits

Although many do not think about it, the mechanics behind how we chew our food can alter the position of the sphenoid bone in time. Utilizing the pterygoids, temporalis, and chewing in all three dimensional planes is the anatomical bio-mechanics of chewing. This translates to the jaw moving laterally, forwards, backwards, and in circles, in rhythm while chewing. Unfortunately, many of the refined foods of today do not require such grinding, and instead contribute to atrophy and amnesia of this bodily process.

One can learn to practice good chewing mechanics by eating fiber rich foods such as nuts, seeds, whole vegetables, and even fruit. The fibrous content of such foods requires the complete range of motion at the jaw and tongue to be achieved. Because chewing is an innate movement, it is backwards to attempt to fix with various isolation exercises. While exercises can help to cultivate awareness, the most powerful moderator of any bodily are the habits we practice from moment to moment.

Swallowing Habits

Given the musculature relationship with the sphenoid, how one swallows can alter the position of the bone. Most importantly, one should practice utilizing the muscles located in the soft palate and pharynx, instead of the cheeks. By doing what is known as a “Mona Lisa swallow”, keep the lips and cheeks still and use the pharyngeal constrictors located in the back of the throat to swallow. This exercise will help to better position the sphenoid as the proper muscles are being stimulated for such an action. When this becomes too easy try swallowing with the tip of your tongue outside of your mouth. Doing so will force the tongue and larynx into a more difficult position, making the actual act of swallowing somewhat easier.

Conclusion

The seemingly unknown sphenoid bone can impede on the experience of life for any individual. Disorders of posture, breathing, stress, and balance, could all be the result of a dysfunctional sphenoid bone. Worse yet, this reality is often unknown to the vast majority of healthcare professionals and can be left undiagnosed for quite some time. Being aware, while practicing good breathing/swallowing/chewing mechanics is the most powerful and long lasting answer to the sphenoid question. While almost too simple to be true, the fact of the matter is that in this modern world we have forgotten the most simple facets of being human.

References

- di Vico, R., Ardigò, L. P., Salernitano, G., Chamari, K., & Padulo, J. (2014). The acute effect of the tongue position in the mouth on knee isokinetic test performance: a highly surprising pilot study. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal, 3(4), 318–323.

- Kjetil Larsen. (2017, March 24). The true cause and solution for temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) – Treningogrehab.no. Retrieved December 18, 2019, from Treningogrehab.no website: https://treningogrehab.no/true-cause-solution-temporomandibular-dysfunction-tmd/

- Eby, G. A. (2006). Strong humming for one hour daily to terminate chronic rhinosinusitis in four days: A case report and hypothesis for action by stimulation of endogenous nasal nitric oxide production. Medical Hypotheses, 66(4), 851–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2005.11.035

- Saaresranta, T., & Polo, O. (2003). Sleep-disordered breathing and hormones. European Respiratory Journal, 22(1), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.03.00062403

- Wetterberg, L. (1983). The relationship between the pineal gland and the pituitary-adrenal axis in health, endocrine and psychiatric conditions. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 8(1), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4530(83)90042-2